Over the past couple of months, there has been a parade of “reasoning” models: DeepSeek-R1, OpenAI’s o3, Alibaba’s QwQ, and now Grok 3. Each announcement follows a similar pattern: impressive benchmark scores on math competitions, science exams, and coding challenges, with claims about moving closer to AGI. Just this week, Elon Musk announced Grok 3 as the “smartest AI on earth,” using benchmarks on reasoning tasks. But what exactly do we mean when we talk about reasoning in AI?

This question matters because reasoning has become the new frontier in AI development. The race to build models that can solve complex problems through step-by-step thinking has supplanted earlier focus around how large language models are, or how much information they could process. François Chollet’s ARC Prize competition explicitly positioned reasoning as a “north star for AGI” development, backing it with a million dollar prize. Benchmarks based on academic competitions or standardized tests like AIME, MATH-500, and GPQA have become the gauntlet that every new AI model must pass through to prove its worth.

Reasoning, in the human sense, usually means the ability to arrive at a conclusion in a rigorous way. It involves exploring multiple approaches, verifying solutions, and adapting strategies on the fly. To do this automatically, large language models (LLMs) are used to recombine knowledge gained during training in order to solve new, unseen problems. It is therefore different from simply retrieving memorized patterns from training data. When DeepSeek describes their R1 model as “naturally emerging with numerous powerful and interesting reasoning behaviors” after reinforcement learning, they’re highlighting this distinction.

So, let’s discuss reasoning - what it is, how we measure it, and how AI systems do reasoning. Given the scope of this topic, I’ll be breaking it down into separate posts1. In this post, I’ll clarify what we mean by reasoning, how it’s measured, and where current AI systems are. Future posts will examine how AI models are trained towards reasoning capabilities, and how models generate reasoning at test time, including the computational trade-offs involved. My goal isn’t to hype up the latest benchmark scores, but to understand what these developments mean for AI’s capabilities and limitations.

Math: The Standard for Measuring Reasoning

Problems in mathematics typically have unambiguous correct answers and require multiple steps of logical deduction, making them great for measuring reasoning. The American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME) is an example of this; it is now a standard AI benchmark. Designed for high school students who excel at mathematics, AIME consists of fifteen questions to be solved in a three-hour period, with each answer being an integer between 0 and 999. A typical student might solve five questions correctly—about 30% accuracy. The MATH-500 benchmark, consisting of 500 competition-level math problems, provides a similar test bed, but I’ll focus on AIME.

Here is an example problem from AIME 2024:

Every morning Aya goes for a 9-kilometer-long walk and stops at a coffee shop afterwards. When she walks at a constant speed of s kilometers per hour, the walk takes her 4 hours, including t minutes spent in the coffee shop. When she walks s+2 kilometers per hour, the walk takes her 2 hours and 24 minutes, including t minutes spent in the coffee shop. Suppose Aya walks at s+1/2 kilometers per hour. Find the number of minutes the walk takes her, including the t minutes spent in the coffee shop."

Solving this requires setting up equations, solving for multiple unknowns, and substituting values—precisely the kind of multi-step reasoning process we want to measure. Here is another example from AIME 2024:

There exist real numbers x and y, both greater than 1, such that log₍ₓ₎(y^x) = log₍y₎(x^4y) = 10. Find xy."

This requires manipulating logarithmic expressions, solving systems of equations, and finding the final product—steps requiring both technical knowledge and creative problem-solving. So can LLMs solve these sort of problems? Yes, mostly2:

| Model | AIME 2024 Score |

|---|---|

| Claude Sonnet (no search) | 16.0% |

| DeepSeek-V3 (no search) | 39.2% |

| Grok 3 (no search) | 52.2% |

| DeepSeek-R1 | 79.8% |

| OpenAI-o1 | 83.3% |

| OpenAI-o3 | 87.3% |

| Grok 3 | 93.3% |

Most state-of-the-art models significantly outperform typical human test-takers, with Grok 3 claiming to solve nearly every problem correctly. However, approach these results with caution. While math benchmarks are frequently updated, by using new competition questions, for example, the questions can be reused from other sources online. This is the problem of leakage: LLMs are trained on massive internet datasets, so if a question is present in their training data, it is like getting the test before taking it. As pointed out by Dimitris Papailiopoulos, questions from this year’s AIME competition, or ones that are nearly identical to them, can be found online.

Even so, the progress from previous models like gpt-4o, or models not using search, show that there is more here than just regurgitating the training data. With reasoning methods, LLMs are able to greatly outperform the average performance of human competitors on these math problems.

Code: Reasoning in the Real World

While the mathematical results are interesting, most uses of LLMs are not intended to calculate the number of minutes someone walks as they get coffee. A common use-case for LLMs so far has been in coding assistance, motivating the inclusion of coding benchmarks that test an LLM’s ability to solve programming challenges, debug existing code, and implement algorithms. Among the most prominent are Codeforces (a competitive programming platform), SWE-Bench (which uses real GitHub issues), and LiveCodeBench (which evaluates models on fresh coding questions). These benchmarks measure not just the ability to write code that compiles, but code that correctly implements a solution to a problem - often requiring multiple steps of reasoning about data structures, algorithms, and edge cases.

What makes coding benchmarks particularly interesting is their real-world applicability. SWE-Bench draws from actual GitHub issues in popular repositories. When an engineer files an issue like “Bug: parse_parameters fails when param contains curly braces,” they’ve already done significant reasoning to identify where the problem might be occurring. The LLM’s task becomes more focused - understand the codebase, locate the bug, and implement a fix. This mirrors how AI coding assistants are actually used in practice: as collaborative tools that augment human reasoning rather than replace it entirely.

Consider this example from SWE-Bench where a model must fix a bug in the Sphinx documentation generator. The issue describes that the Napoleon extension isn’t properly formatting the “Other Parameters” keyword when a specific configuration setting is enabled. To resolve this, the model must understand the codebase structure, identify the relevant function (_parse_other_parameters_section), understand how it interacts with the configuration setting, and implement a fix that addresses the issue without breaking existing functionality. The challenge lies not in writing code from scratch, but in reasoning about an existing codebase with thousands of files and complex interdependencies.

Here is how models perform on SWE-Bench Verified3:

| Model | SWE-Bench Verified Score |

|---|---|

| Claude Sonnet | 50.8% |

| OpenAI-o1 | 48.9% |

| DeepSeek-R1 | 49.2% |

These scores might appear impressive, but they should be contextualized. SWE-Bench researchers asked software engineering experts to estimate how long it would take to solve these issues, and 77.8% of the samples were estimated to require less than an hour for an experienced engineer. The current scores suggest models can resolve about half of these simpler issues automatically, making them valuable assistants but not yet capable of autonomously handling complex software engineering tasks. The takeaway is that while coding presents a practical application of reasoning capabilities, even the best models still struggle with real-world software engineering tasks that require deep contextual understanding across large codebases.

Science: Advanced Knowledge Meets Reasoning

A third category often used for testing LLM reasoning is scientific questioning. While math and coding focus primarily on pure reasoning, scientific problems blend factual knowledge with deductive logic. A standard benchmark for AI in scientific reasoning is the Google-Proof Question Answering (GPQA) benchmark. Released by Google DeepMind, GPQA features graduate-level science questions that resist simple Google searches—you need both deep domain knowledge and the ability to reason through complex scientific scenarios to solve them.

GPQA’s “Diamond” subset represents especially challenging questions across biology, chemistry, and physics. Here is an example chemistry question4:

Methylcyclopentadiene (which exists as a fluxional mixture of isomers) was allowed to react with methyl isoamyl ketone and a catalytic amount of pyrrolidine. A bright yellow, cross-conjugated polyalkenyl hydrocarbon product formed (as a mixture of isomers), with water as a side product. These products are derivatives of fulvene. This product was then allowed to react with ethyl acrylate in a 1:1 ratio. Upon completion of the reaction, the bright yellow color had disappeared. How many chemically distinct isomers make up the final product (not counting stereoisomers)?

A) 2

B) 16

C) 8

D) 4

And an example astronomy question:

Astronomers are studying a star with a Teff of approximately 6000 K. They are interested in spectroscopically determining the surface gravity of the star using spectral lines (EW < 100 mA) of two chemical elements, El1 and El2. Given the atmospheric temperature of the star, El1 is mostly in the neutral phase, while El2 is mostly ionized. Which lines are the most sensitive to surface gravity for the astronomers to consider?

A) El2 I (neutral)

B) El1 II (singly ionized)

C) El2 II (singly ionized)

D) El1 I (neutral)

Answering these questions requires both recalling specialized scientific knowledge and applying multi-step reasoning about chemical reactions or stellar physics. Current LLMs do well on GPQA Diamond5:

| Source | GPQA Diamond Score |

|---|---|

| Human experts | 81.2% |

| Non-expert humans | 21.9% |

| Claude Sonnet | 65.0% |

| DeepSeek-R1 | 71.5% |

| OpenAI-o1 | 78.0% |

| OpenAI-o3 | 79.7% |

| Grok 3 | 84.6% |

All major LLMs significantly outperform non-expert humans, and Grok 3 even claims to surpass the average performance of human experts. This suggests that today’s most advanced AI systems possess scientific knowledge comparable to graduate students or early-career scientists, while maintaining the reasoning capabilities to apply this knowledge correctly.

The scientific domain represents an interesting middle ground in AI reasoning. Unlike pure math problems where the challenge is primarily in the reasoning process, scientific questions require merging broad factual knowledge with abstract reasoning. This is maybe what LLMs are best at: memorizing huge amounts of information and deploying that information in contextually appropriate ways.

Visual Reasoning: The Frontier Challenge

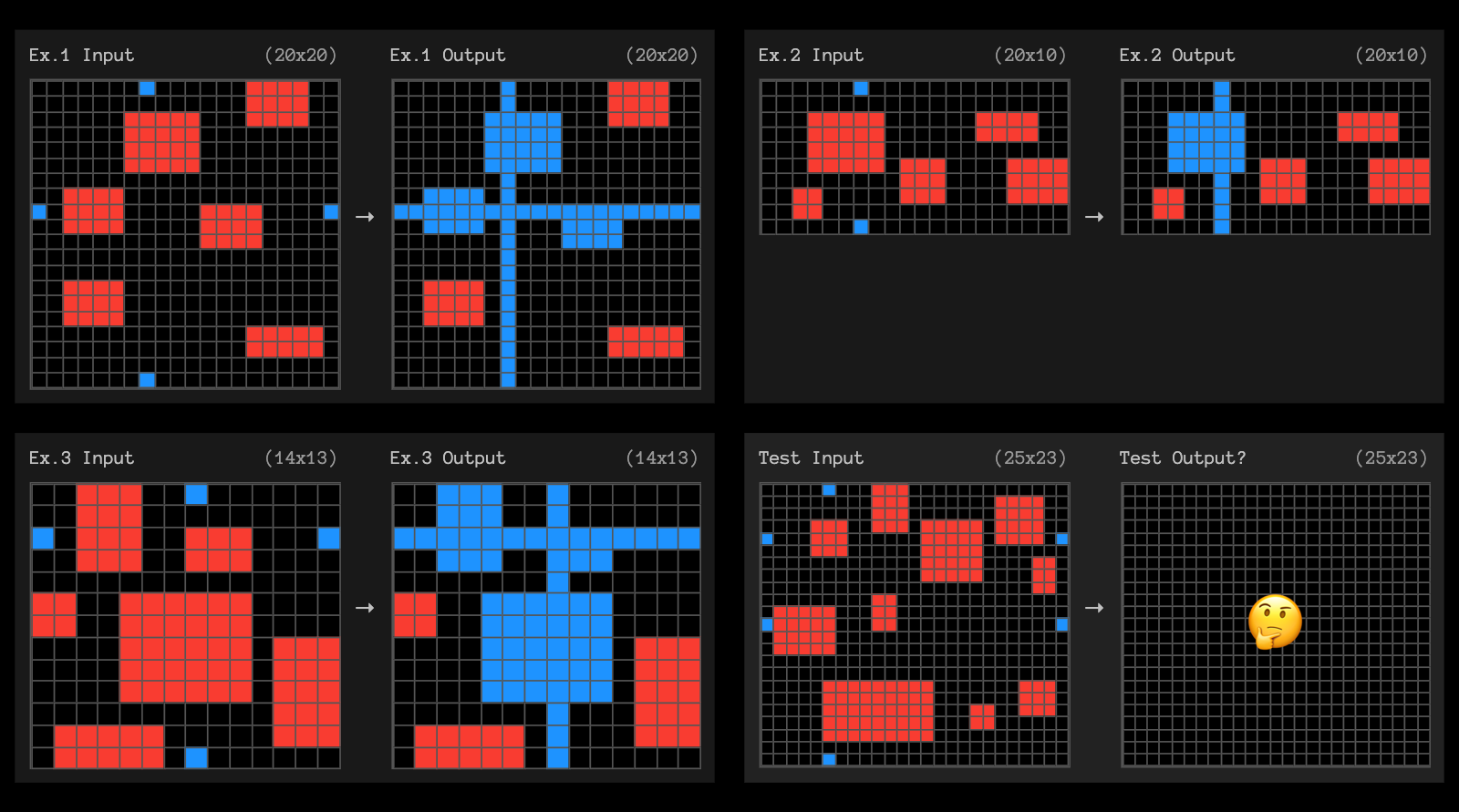

While language models are good at scientific reasoning, they struggle significantly with visual reasoning tasks. The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC), developed by François Chollet, presents a fundamentally different challenge than traditional reasoning benchmarks. ARC tasks require models to infer underlying rules from visual examples and apply them to new instances—a type of reasoning that’s intuitive for humans but surprisingly difficult for AI.

What makes ARC particularly challenging is that it tests pure reasoning about shapes, patterns, and transformations without relying on prior knowledge. Each puzzle consists of a few example transformations (input grid → output grid), and the model must deduce the underlying rule to transform a new input grid. These tasks specifically avoid specialized knowledge, focusing instead on core reasoning capabilities that humans develop early in life.

For ARC, current approaches typically convert images into text descriptions or ASCII representations, essentially translating the visual problem into language. This conversion loses spatial information and relationships that are crucial for solving these puzzles. Even the most advanced vision-language models have made little progress on this front. As Gary Marcus pointed out in his recent critique of Grok 3, these models still struggle with basic visual pattern recognition and transformation tasks.

An example is the ARC puzzle 0d87d2a6, which remains unsolved by OpenAI’s o3 even with extensive computation. This puzzle requires tracing paths from grid edges and recoloring squares where paths intersect—a task that combines spatial reasoning with rule inference in a way that’s particularly challenging for current AI approaches.

Here, models trained for reasoning like DeepSeek-r1 and OpenAI’s o1 fall far from human performance6:

| Model | ARC-AGI-1 Score |

|---|---|

| Human baseline | 85.0% |

| DeepSeek-r1 | 14.0% |

| OpenAI-o1 | 35.0% |

| OpenAI-o3 (standard) | 75.7% |

| OpenAI-o3 (high compute) | 87.5% |

While o3’s high-compute performance appears competitive with humans, this comes at a huge cost—about $17 per task under standard settings, scaling to an estimated $3,400 per task for the highest performance configuration. For the 400-task public evaluation set, that’s more than a million dollars in computation costs. Good thing there’s a million dollar prize!

The visual reasoning frontier reveals a fundamental limitation in current AI systems. Despite good performance on mathematical, coding, and scientific reasoning tasks, these models still lack the intuitive visual understanding that humans develop naturally. Humans naturally understand visual information; our brains are hard-wired for it. This is Moravec’s Paradox; tasks humans find difficult, like playing chess or solving complex equations, are relatively easy for AI, while tasks humans find easy, like walking, recognizing faces, or understanding natural language, are surprisingly hard for AI. As Rodney Brooks put it, elephants don’t play chess.

From Reasoning to Utility

So after passing LLMs through a guantlet of standardized tests, what do we understand about their capabilities? Modern LLMs are certainly impressive in domains like mathematics and science, where they can match or exceed human expert performance. This suggests that for certain well-defined problem spaces with clear evaluation criteria, AI is capable of reasoning as we understand it.

However, we should remember that these models remain fundamentally stochastic systems, and that they’re trained bullshitters. Models can produce convincing-sounding explanations that contain subtle errors or hallucinations. The chain of thought might appear logical and well-reasoned, yet contain faulty premises or incorrect steps that are difficult to catch without domain expertise. This tendency to generate plausible-sounding but incorrect reasoning remains a huge problem, even as the quality of reasoning improves on these benchmarks. Just because Grok can reason about math problems better doesn’t mean that it will reasonably answer your questions; it might just be better at gaslighting you.

I also find that there’s a concerning shift in priorities in AI. Last year, the focus was predominantly on alignment—using reinforcement learning to ensure AI systems adhered to human values and preferences. Now, the drive is fully toward pure reasoning capabilities, sometimes at the expense of alignment considerations. Like DeepSeek’s R1: it tanked NVIDIA’s stock because of its impressive reasoning performance, while issues around its heavy political bias were secondary. Some benchmarks like Chatbot Arena still focus on human preference alignment alongside reasoning, but the industry’s primary focus has clearly shifted toward reasoning capabilities.

This raises an important question: does our current approach to measuring “intelligence” in LLMs align with how we actually want to use these systems? For coding assistance, absolutely—programmers benefit directly from models that can reason through complex software engineering problems. But most people aren’t using LLMs to solve AIME problems or answer graduate-level chemistry questions. Going forward, a greater focus has to be on how these systems can be useful to people. As we define benchmarks and development priorities, we should make sure that they reflect the real-world utility we want from AI.

After a busy year of submitting an ERC grant and an HDR, I’m back to writing blog posts. To keep a reasonable rhythm, I’m planning some series on topics that I hope will still be relevant by the time I finish them. This first one is on reasoning. ↩︎

Scores from DeepSeek-R1 preprint and Grok 3 post. ↩︎

Scores from DeepSeek-R1 preprint. Grok 3 was tested on a different benchmark (LiveCodeBench) where it reportedly showed improvement over o1. ↩︎

Both example questions from Rein, David, et al. “Gpqa: A graduate-level google-proof q&a benchmark.” ↩︎

Scores from DeepSeek-R1 preprint and Grok 3 post. ↩︎

Scores from ARC-AGI Prize. ↩︎