Since the release of ChatGPT, Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Llama have become ubiquitous in our daily lives. These models generate text, code, or even images. In this post, I’ll give a high-level introduction1 to Large Language Models, the technical details about them as well as the current challenges facing them. In future posts, I’ll go into more detail about how they are being used and some of the challenges overviewed here.

Large Language Models

The backbone of Large Language Models is the artificial neural network or ANN. Inspired by the human brain, ANNs have been studied since the 1940s. These models simulate interconnected artificial neurons, with parameters defining their connections. Learning occurs through backpropagation, which compares a model’s output to the desired one.

Consider, for example, the sentence: “This cat is cute.” We can give the model the beginning of the sentence, “this cat is”, and use the model to generate the last word. If the model outputs “cute,” we consider the model parameters to be good and don’t make major changes to them. But if the model outputs something else, we use backpropagation to adjust the parameters so that it is more likely to output “cute” the next time.

This loop of using an ANN model, comparing its output to data, and adjusting the parameters is known as “learning” or “training.” Training depends heavily on data to demonstrate what outputs we expect from a model. This data dependence is especially important for generative AI, where multiple good outputs often exist. For example, the final word of the sentence “This cat is cute” could also be “pretty” or “adorable.” How do we encourage the model to generate these diverse, yet sensible, responses while avoiding nonsensical ones like “This cat is sandwich”?

The specific ANN architecture behind LLMs is called a “Transformer” architecture. The modern transformer architecture was developed in 2017 and transforms one data sequence into another. A sequence can be, for example, a sentence or multiple sentences. LLMs use an “attention” mechanism to identify the most crucial parts of the input sequence. For instance, to predict “cute” in “This cat is cute,” the model focuses on “cat” more than “this” or “is.” This allows transformers to handle large amounts of context without internal memory, relying instead on a large input sequence.

An important characteristic of LLMs is that they are “large” – much larger than previous neural networks. GPT2, an early version of the mode behind ChatGPT, had 1.5 billion parameters, and speculated numbers for the parameter counts of GPT3.5 and GPT4, the current ChatGPT models, range from 20 billion to 1.7 trillion. Training such a massive model requires a similarly massive amount of data.

Next token prediction

The standard training approach for LLMs is next token prediction: giving the model most of a sentence and using it to predict the next word. Using the example of “This cat is”, the model is asked using next-token prediction to predict “cute,” the next token. LLMs operate on “tokens” instead of words, to take characters and word segments into account. A token might be a word, a part of a word, a punctuation mark, a word with a space before it, a word with a suffix. The “vocabulary” of a model is the set of all possible tokens it can generate; the vocabulary of GPT2 and GPT3 is 50257 tokens, ranging from logical ones like “The” to surprising ones like “davidjil”.

To train these giant models on next-token prediction, AI companies like OpenAI turned to the vast public internet. Datasets of sentences were gathered, with GPT-3 having a training set of over 500 billion tokens. To give an idea of the size, all of Wikipedia is only 3 billion tokens out of the 500 billion. The large size of these datasets and the language models trained on them is a recent development in AI.

So now, we can understand the name of ChatGPT, which stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. “Generative” because it generates text, “Pre-trained” because it’s already been trained, and “Transformer” because of its neural network architecture. By training a large language model on billions of tokens and evaluating its ability to predict language tokens, the model learns to produce surprisingly intelligent-seeming results. However, this training method on public internet data and the use of next-token prediction cause many problems, such as biases, generating false information, the plateauing of performance, and legal issues.

Bias

One of the largest and inherent issues in language models is bias. Bias is what models use to make accurate predictions. A model trained on data which frequently says that cats are cute will learn to predict the sentence “This cat is cute” more often than “This cat is ugly”: we could say that the model has a positive bias towards cats.

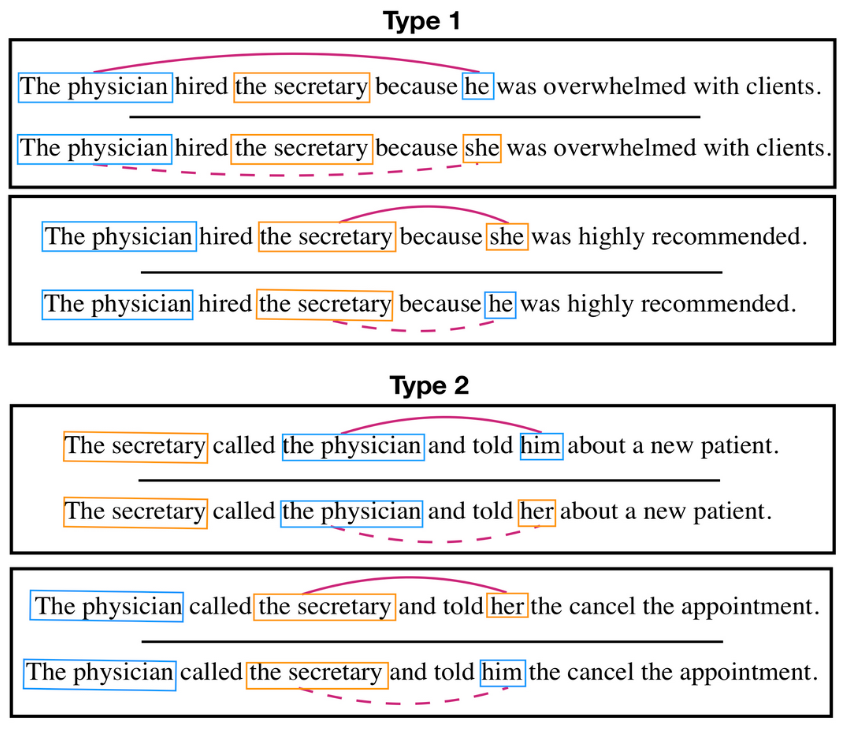

The data used to train these models comes from the public internet, so it contains biases that are prevalent on the internet. Gender stereotypes and cultural prejudices seep into the model’s predictions, leading to biased outputs. For example, a model trained on internet data will predict that a farmer is male and a nurse is female.

To mitigate bias, the commonly used method is reinforcement learning with human feedback, where human annotations of generated text are used to determine when a response is appropriate or not. However, as witnessed recently with Google’s Gemini model, aligning generative AI with human values means defining a specific set of values. What is considered good or appropriate varies across cultures and individuals, making it difficult to establish a universal standard. As Irene Solaiman has said, “bias can never be fully solved as an engineering problem… Bias is a systemic problem.”

Hallucinations

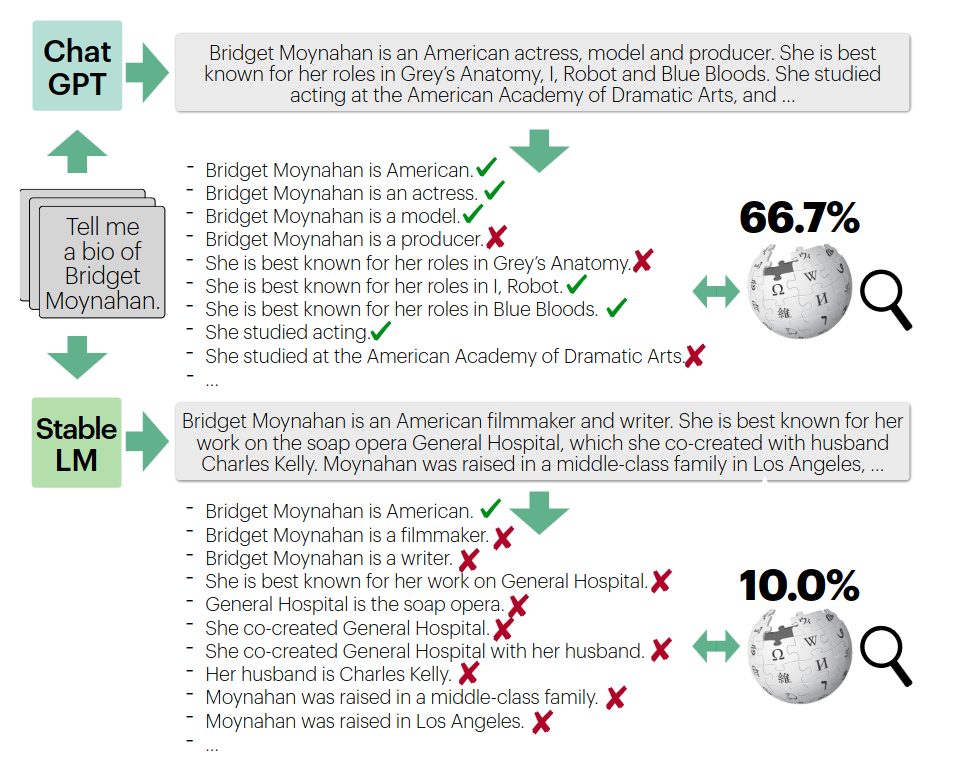

Another critical issue is the ability of LLMs to generate text which is false, while still sounding factual. Without fact-checking mechanisms, these models often generate misleading or false information, as they are only predicting the next token. These false statements are often referred to as hallucinations.

For instance, Google’s announcement of their Bard model contained an erroneous claim about the first image of an exoplanet ever taken. A simple Google search shows that the real first image was from 20 years ago, not recently as was claimed in the generated text.

While efforts like tying generated content to verified sources are being studied, fully resolving this issue remains challenging and it isn’t clear if it’s even possible. The most common solution currently is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), which combines an LLM with a retrieval model to ensure that the generated text is based on verified sources. While RAG has shown promise in reducing hallucinations, state-of-the-art RAG methods show that there is still much work to be done.

Public internet data

The reliance on publicly available internet data for training LLMs also creates a number of challenges. Future generative AI models may not offer significant performance improvements without new technological breakthroughs. It is worth noting that next-token prediction was formulated in 1950, the attention mechanism for neural networks in 2014, and the transformer architecture in 2017. The recent development of LLMs is due to tapping into a limited resource, publicly available text, which may not be sustainable. For example, if the public internet fills with more AI-generated content, the performance of these models may even decrease. Researchers have claimed that some language models are already decreasing in quality over time.

Furthermore, utilizing copyrighted internet data raises legal concerns. This has resulted in a number of lawsuits from news organizations like the New York Times and authors like George R. R. Martin against AI companies.

Future opportunities and challenges

LLMs are now being used in a variety of applications, from assisting users in finding information on websites, to autocompletion in writing tasks, even to offering medical advice based on scans and images of the human body. Open source LLMs allow for integration of these models into a wide range of applications. A clear direction for future generative AI applications is linking LLMs with other software, such as internet search or voice recognition, to create more seamless and natural interactions. However, the challenges described above of bias, hallucinations, plateauing performance, and legal issues will need to be addressed as LLMs are integrated into more applications.

Introductory posts like this one will help me keep a more regular schedule, so please let know in the comments what you think about this format. ↩︎